To understand what "sharpening" a knife actually means, it is necessary to understand what makes a knife dull in the first place. When brand new or freshly sharpened, a knife's edge should possess a crisp apex with minimal surface area at the top (i.e. pointy). Through normal use however, this apex takes on a more rounded, smoothened and plateaued appearance. This is because each time a knife's edge hits the surface a cutting board, it deforms or bends slightly. The rate of which this deformation occurs depends on two things: (1) the hardness of the knife edge itself, and (2) hardness of the cutting board. The harder the cutting board and the softer the metal at the knife edge, the easier it is for the edge to deform. This is why a soft cutting board is equally as important as an excellently heat-treated knife, and also the reason why chopping anything on a serving/dinner plate is an incredibly foolish idea.

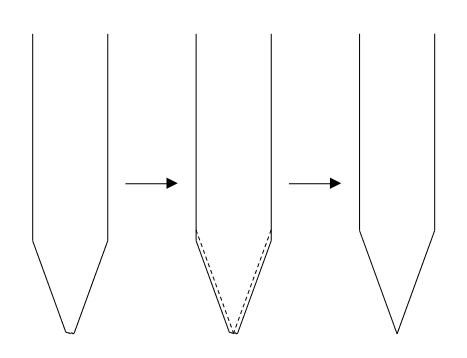

Now that you understand what constitutes a dull knife, you can see that when I "sharpen" a knife, what I am really doing is simply restoring that clean, crisp apex. This process is illustrated in the (poorly-drawn) figure above, and is done using a succession of whetstones in order of increasing grit size, or fineness.

Whetstone progression

For a really flattened or nonexistent apex (trust me, I've seen things), I begin sharpening with a coarse (200-400 grit) stone to help quickly establish the main shape of the apex. Now, this leaves the peak of the apex rather jagged or toothy; indeed, if you look closely with a loupe, you'll be able to see microserrations on the edge, and this is what enables you to saw your way through those pesky tomato skins. However, edges that are overly jagged would not be ideal for cutting delicate foods such as basil or raw fish. The cells would get caught on the edge and get pulled out rather than sliced cleanly, leaving more than necessary amounts of flavour-rich juices on the cutting board. To remedy this, the apex is refined using a medium (800-2000 grit) stone. This is the point where I stop for most knives.However, for knives that have been heat-treated to a higher level of hardness (typical of Japanese-made knives), I go through the extra step of further polishing the edge with a fine (above 2000 grit) stone. This step is not carried out on knives heat-treated to a lower hardness level as it would actually be detrimental to their performance. Remember, the apex of softer knives are more easily deformed and rounded-off. If they were to be finished on a fine 5000 grit stone, the resulting finer microserrations on the edge would be smoothened out very quickly with just a few hits on the chopping board, leaving you with a knife that slips and slides on tomato skins, even though it may be hair-shaving sharp. It is thus completely futile to go beyond 2000 grit for most knives; there is an optimal finishing grit to be aimed for, and lower finishing grits that create toothier edges are desirable for softer knives.

Stones that I use

I myself have amassed quite an impressive collection of whetstones being a knife sharpener, but here are the main ones that I use when sharpening for my customers (and the grit progression):

Naniwa Chosera #400 > Suehiro CERAX #1000 > (if appropriate) Suehiro Rika #5000

Stropping

After sharpening, each blade is gently stropped on leather loaded with green compound. This is the final step. What this does is it removes the fine wire edge (also known as a burr) invisible to the naked eye hanging off the knife edge, formed when metal is ground away at the edge. Stropping cleans up the edge and ensures that the blade retains its sharpness for as long as possible.

In summary...

The sharpening method that I employ is not overwhelmingly complex nor difficult. It is more or less the same as how a butcher or chef sharpens their knives, and I truly believe that anyone can learn how to do my job such that they would never ever require my service. Having said that, my role here is to give you the option to save yourself some time and effort in maintaining your knives. A lot of my customers who are chefs do in fact, know how to sharpen their own knives; they just can't be bothered after an exhausting evening service.

Return to homepage

Return to homepage